Hardware Memory Models

这是 Go 语言现任领队 Russ Cox 在 2021 年写的文章 Hardware Memory Models 的英文原版的备份。

本文是第一篇,重点阐述了几个流行的 ISA(指令集架构)中如何实现缓存同步;第二篇则是总结了常见的支持多线程的语言中同步设施(内存模型)的设计;第三篇则讲述了 Go 的内存模型,Go 的内存模型已经于去年正式发布。

Hardware Memory Models

(Memory Models, Part 1)

Posted on Tuesday, June 29, 2021.

Introduction: A Fairy Tale, Ending

A long time ago, when everyone wrote single-threaded programs, one of the most effective ways to make a program run faster was to sit back and do nothing. Optimizations in the next generation of hardware and the next generation of compilers would make the program run exactly as before, just faster. During this fairy-tale period, there was an easy test for whether an optimization was valid: if programmers couldn’t tell the difference (except for the speedup) between the unoptimized and optimized execution of a valid program, then the optimization was valid. That is, valid optimizations do not change the behavior of valid programs.

One sad day, years ago, the hardware engineers’ magic spells for making individual processors faster and faster stopped working. In response, they found a new magic spell that let them create computers with more and more processors, and operating systems exposed this hardware parallelism to programmers in the abstraction of threads. This new magic spell—multiple processors made available in the form of operating-system threads—worked much better for the hardware engineers, but it created significant problems for language designers, compiler writers and programmers.

Many hardware and compiler optimizations that were invisible (and therefore valid) in single-threaded programs produce visible changes in multithreaded programs. If valid optimizations do not change the behavior of valid programs, then either these optimizations or the existing programs must be declared invalid. Which will it be, and how can we decide?

Here is a simple example program in a C-like language. In this program and in all programs we will consider, all variables are initially set to zero.

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

x = 1; while\(done == 0\) \{ /\* loop \*/ \}

done = 1; print\(x\);

If thread 1 and thread 2, each running on its own dedicated processor, both run to completion, can this program print 0?

It depends. It depends on the hardware, and it depends on the compiler. A direct line-for-line translation to assembly run on an x86 multiprocessor will always print 1. But a direct line-for-line translation to assembly run on an ARM or POWER multiprocessor can print 0. Also, no matter what the underlying hardware, standard compiler optimizations could make this program print 0 or go into an infinite loop.

“It depends” is not a happy ending. Programmers need a clear answer to whether a program will continue to work with new hardware and new compilers. And hardware designers and compiler developers need a clear answer to how precisely the hardware and compiled code are allowed to behave when executing a given program. Because the main issue here is the visibility and consistency of changes to data stored in memory, that contract is called the memory consistency model or just memory model.

Originally, the goal of a memory model was to define what hardware guaranteed to a programmer writing assembly code. In that setting, the compiler is not involved. Twenty-five years ago, people started trying to write memory models defining what a high-level programming language like Java or C++ guarantees to programmers writing code in that language. Including the compiler in the model makes the job of defining a reasonable model much more complicated.

This is the first of a pair of posts about hardware memory models and programming language memory models, respectively. My goal in writing these posts is to build up background for discussing potential changes we might want to make in Go’s memory model. But to understand where Go is and where we might want to head, first we have to understand where other hardware memory models and language memory models are today and the precarious paths they took to get there.

Again, this post is about hardware. Let’s assume we are writing assembly language for a multiprocessor computer. What guarantees do programmers need from the computer hardware in order to write correct programs? Computer scientists have been searching for good answers to this question for over forty years.

Sequential Consistency

Leslie Lamport’s 1979 paper “How to Make a Multiprocessor Computer That Correctly Executes Multiprocess Programs” introduced the concept of sequential consistency:

The customary approach to designing and proving the correctness of multiprocess algorithms for such a computer assumes that the following condition is satisfied: the result of any execution is the same as if the operations of all the processors were executed in some sequential order, and the operations of each individual processor appear in this sequence in the order specified by its program. A multiprocessor satisfying this condition will be called sequentially consistent.

Today we talk about not just computer hardware but also programming languages guaranteeing sequential consistency, when the only possible executions of a program correspond to some kind of interleaving of thread operations into a sequential execution. Sequential consistency is usually considered the ideal model, the one most natural for programmers to work with. It lets you assume programs execute in the order they appear on the page, and the executions of individual threads are simply interleaved in some order but not otherwise rearranged.

One might reasonably question whether sequential consistency should be the ideal model, but that’s beyond the scope of this post. I will note only that considering all possible thread interleavings remains, today as in 1979, “the customary approach to designing and proving the correctness of multiprocess algorithms.” In the intervening four decades, nothing has replaced it.

Earlier I asked whether this program can print 0:

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

x = 1; while\(done == 0\) \{ /\* loop \*/ \}

done = 1; print\(x\);

To make the program a bit easier to analyze, let’s remove the loop and the print and ask about the possible results from reading the shared variables:

Litmus Test: Message Passing

Can this program see

r1=1,r2=0?

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

x = 1 r1 = y

y = 1 r2 = x

We assume every example starts with all shared variables set to zero. Because we’re trying to establish what hardware is allowed to do, we assume that each thread is executing on its own dedicated processor and that there’s no compiler to reorder what happens in the thread: the instructions in the listings are the instructions the processor executes. The name rN denotes a thread-local register, not a shared variable, and we ask whether a particular setting of thread-local registers is possible at the end of an execution.

This kind of question about execution results for a sample program is called a litmus test. Because it has a binary answer—is this outcome possible or not?—a litmus test gives us a clear way to distinguish memory models: if one model allows a particular execution and another does not, the two models are clearly different. Unfortunately, as we will see later, the answer a particular model gives to a particular litmus test is often surprising.

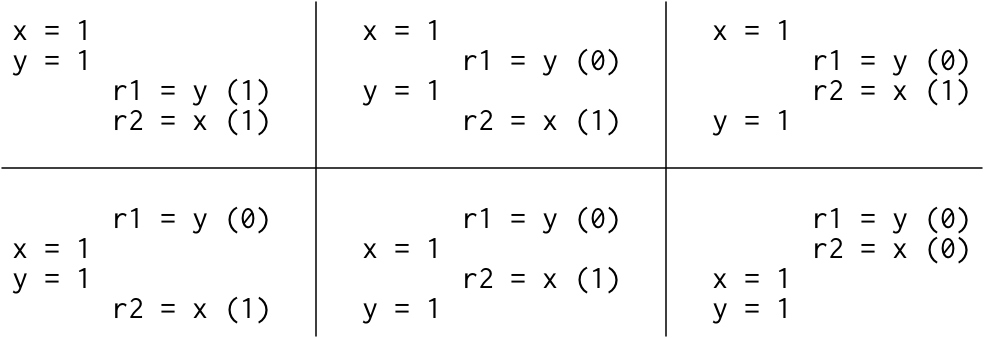

If the execution of this litmus test is sequentially consistent, there are only six possible interleavings:

Since no interleaving ends with r1 = 1, r2 = 0, that result is disallowed. That is, on sequentially consistent hardware, the answer to the litmus test—can this program see r1 = 1, r2 = 0?—is no.

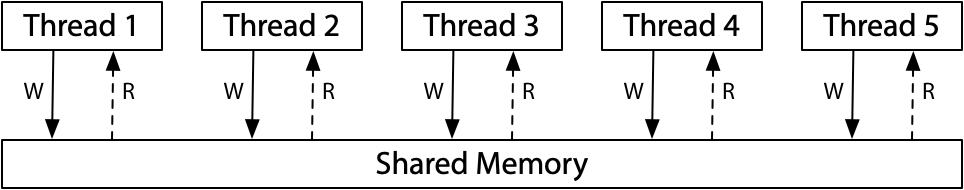

A good mental model for sequential consistency is to imagine all the processors connected directly to the same shared memory, which can serve a read or write request from one thread at a time. There are no caches involved, so every time a processor needs to read from or write to memory, that request goes to the shared memory. The single-use-at-a-time shared memory imposes a sequential order on the execution of all the memory accesses: sequential consistency.

(The three memory model hardware diagrams in this post are adapted from Maranget et al., “A Tutorial Introduction to the ARM and POWER Relaxed Memory Models.”)

This diagram is a model for a sequentially consistent machine, not the only way to build one. Indeed, it is possible to build a sequentially consistent machine using multiple shared memory modules and caches to help predict the result of memory fetches, but being sequentially consistent means that machine must behave indistinguishably from this model. If we are simply trying to understand what sequentially consistent execution means, we can ignore all of those possible implementation complications and think about this one model.

Unfortunately for us as programmers, giving up strict sequential consistency can let hardware execute programs faster, so all modern hardware deviates in various ways from sequential consistency. Defining exactly how specific hardware deviates turns out to be quite difficult. This post uses as two examples two memory models present in today’s widely-used hardware: that of the x86, and that of the ARM and POWER processor families.

x86 Total Store Order (x86-TSO)

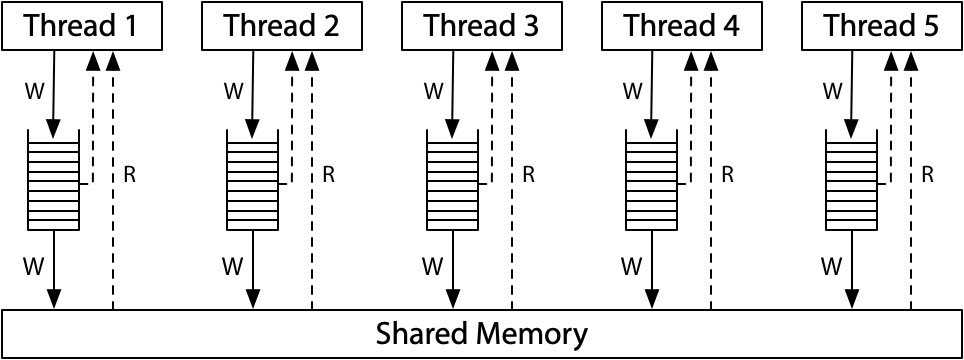

The memory model for modern x86 systems corresponds to this hardware diagram:

All the processors are still connected to a single shared memory, but each processor queues writes to that memory in a local write queue. The processor continues executing new instructions while the writes make their way out to the shared memory. A memory read on one processor consults the local write queue before consulting main memory, but it cannot see the write queues on other processors. The effect is that a processor sees its own writes before others do. But—and this is very important—all processors do agree on the (total) order in which writes (stores) reach the shared memory, giving the model its name: total store order, or TSO. At the moment that a write reaches shared memory, any future read on any processor will see it and use that value (until it is overwritten by a later write, or perhaps by a buffered write from another processor).

The write queue is a standard first-in, first-out queue: the memory writes are applied to the shared memory in the same order that they were executed by the processor. Because the write order is preserved by the write queue, and because other processors see the writes to shared memory immediately, the message passing litmus test we considered earlier has the same outcome as before: r1 = 1, r2 = 0 remains impossible.

Litmus Test: Message Passing

Can this program see

r1=1,r2=0?

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

x = 1 r1 = y

y = 1 r2 = x

On sequentially consistent hardware: no.

On x86 (or other TSO): no.

The write queue guarantees that thread 1 writes x to memory before y, and the system-wide agreement about the order of memory writes (the total store order) guarantees that thread 2 learns of x’s new value before it learns of y’s new value. Therefore it is impossible for r1 = y to see the new y without r2 = x also seeing the new x. The store order is crucial here: thread 1 writes x before y, so thread 2 must not see the write to y before the write to x.

The sequential consistency and TSO models agree in this case, but they disagree about the results of other litmus tests. For example, this is the usual example distinguishing the two models:

Litmus Test: Write Queue (also called Store Buffer)

Can this program see

r1=0,r2=0?

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

x = 1 y = 1

r1 = y r2 = x

On sequentially consistent hardware: no.

On x86 (or other TSO): yes!

In any sequentially consistent execution, either x = 1 or y = 1 must happen first, and then the read in the other thread must observe it, so r1 = 0, r2 = 0 is impossible. But on a TSO system, it can happen that Thread 1 and Thread 2 both queue their writes and then read from memory before either write makes it to memory, so that both reads see zeros.

This example may seem artificial, but using two synchronization variables does happen in well-known synchronization algorithms, such as Dekker’s algorithm or Peterson’s algorithm, as well as ad hoc schemes. They break if one thread isn’t seeing all the writes from another.

To fix algorithms that depend on stronger memory ordering, non-sequentially-consistent hardware supplies explicit instructions called memory barriers (or fences) that can be used to control the ordering. We can add a memory barrier to make sure that each thread flushes its previous write to memory before starting its read:

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

x = 1 y = 1

barrier barrier

r1 = y r2 = x

With the addition of the barriers, r1 = 0, r2 = 0 is again impossible, and Dekker’s or Peterson’s algorithm would then work correctly. There are many kinds of barriers; the details vary from system to system and are beyond the scope of this post. The point is only that barriers exist and give programmers or language implementers a way to force sequentially consistent behavior at critical moments in a program.

One final example, to drive home why the model is called total store order. In the model, there are local write queues but no caches on the read path. Once a write reaches main memory, all processors not only agree that the value is there but also agree about when it arrived relative to writes from other processors. Consider this litmus test:

Litmus Test: Independent Reads of Independent Writes (IRIW)

Can this program see

r1=1,r2=0,r3=1,r4=0?(Can Threads 3 and 4 see

xandychange in different orders?)

// Thread 1 // Thread 2 // Thread 3 // Thread 4

x = 1 y = 1 r1 = x r3 = y

r2 = y r4 = x

On sequentially consistent hardware: no.

On x86 (or other TSO): no.

If Thread 3 sees x change before y, can Thread 4 see y change before x? For x86 and other TSO machines, the answer is no: there is a total order over all stores (writes) to main memory, and all processors agree on that order, subject to the wrinkle that each processor knows about its own writes before they reach main memory.

The Path to x86-TSO

The x86-TSO model seems fairly clean, but the path there was full of roadblocks and wrong turns. In the 1990s, the manuals available for the first x86 multiprocessors said next to nothing about the memory model provided by the hardware.

As one example of the problems, Plan 9 was one of the first true multiprocessor operating systems (without a global kernel lock) to run on the x86. During the port to the multiprocessor Pentium Pro, in 1997, the developers stumbled over unexpected behavior that boiled down to the write queue litmus test. A subtle piece of synchronization code assumed that r1 = 0, r2 = 0 was impossible, and yet it was happening. Worse, the Intel manuals were vague about the memory model details.

In response to a mailing list suggestion that “it’s better to be conservative with locks than to trust hardware designers to do what we expect,” one of the Plan 9 developers explained the problem well:

I certainly agree. We are going to encounter more relaxed ordering in multiprocessors. The question is, what do the hardware designers consider conservative? Forcing an interlock at both the beginning and end of a locked section seems to be pretty conservative to me, but I clearly am not imaginative enough. The Pro manuals go into excruciating detail in describing the caches and what keeps them coherent but don’t seem to care to say anything detailed about execution or read ordering. The truth is that we have no way of knowing whether we’re conservative enough.

During the discussion, an architect at Intel gave an informal explanation of the memory model, pointing out that in theory even multiprocessor 486 and Pentium systems could have produced the r1 = 0, r2 = 0 result, and that the Pentium Pro simply had larger pipelines and write queues that exposed the behavior more often.

The Intel architect also wrote:

Loosely speaking, this means the ordering of events originating from any one processor in the system, as observed by other processors, is always the same. However, different observers are allowed to disagree on the interleaving of events from two or more processors.

Future Intel processors will implement the same memory ordering model.

The claim that “different observers are allowed to disagree on the interleaving of events from two or more processors” is saying that the answer to the IRIW litmus test can answer “yes” on x86, even though in the previous section we saw that x86 answers “no.” How can that be?

The answer appears to be that Intel processors never actually answered “yes” to that litmus test, but at the time the Intel architects were reluctant to make any guarantee for future processors. What little text existed in the architecture manuals made almost no guarantees at all, making it very difficult to program against.

The Plan 9 discussion was not an isolated event. The Linux kernel developers spent over a hundred messages on their mailing list starting in late November 1999 in similar confusion over the guarantees provided by Intel processors.

In response to more and more people running into these difficulties over the decade that followed, a group of architects at Intel took on the task of writing down useful guarantees about processor behavior, for both current and future processors. The first result was the “Intel 64 Architecture Memory Ordering White Paper”, published in August 2007, which aimed to “provide software writers with a clear understanding of the results that different sequences of memory access instructions may produce.” AMD published a similar description later that year in the AMD64 Architecture Programmer’s Manual revision 3.14. These descriptions were based on a model called “total lock order + causal consistency” (TLO+CC), intentionally weaker than TSO. In public talks, the Intel architects said that TLO+CC was “as strong as required but no stronger.” In particular, the model reserved the right for x86 processors to answer “yes” to the IRIW litmus test. Unfortunately, the definition of the memory barrier was not strong enough to reestablish sequentially-consistent memory semantics, even with a barrier after every instruction. Even worse, researchers observed actual Intel x86 hardware violating the TLO+CC model. For example:

Litmus Test: n6 (Paul Loewenstein)

Can this program end with

r1=1,r2=0,x=1?

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

x = 1 y = 1

r1 = x x = 2

r2 = y

On sequentially consistent hardware: no.

On x86 TLO+CC model (2007): no.

On actual x86 hardware: yes!

On x86 TSO model: yes! (Example from x86-TSO paper.)

Revisions to the Intel and AMD specifications later in 2008 guaranteed a “no” to the IRIW case and strengthened the memory barriers but still permitted unexpected behaviors that seem like they could not arise on any reasonable hardware. For example:

Litmus Test: n5

Can this program end with

r1=2,r2=1?

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

x = 1 x = 2

r1 = x r2 = x

On sequentially consistent hardware: no.

On x86 specification (2008): yes!

On actual x86 hardware: no.

On x86 TSO model: no. (Example from x86-TSO paper.)

To address these problems, Owens et al. proposed the x86-TSO model, based on the earlier SPARCv8 TSO model. At the time they claimed that “To the best of our knowledge, x86-TSO is sound, is strong enough to program above, and is broadly in line with the vendors’ intentions.” A few months later Intel and AMD released new manuals broadly adopting this model.

It appears that all Intel processors did implement x86-TSO from the start, even though it took a decade for Intel to decide to commit to that. In retrospect, it is clear that the Intel and AMD architects were struggling with exactly how to write a memory model that left room for future processor optimizations while still making useful guarantees for compiler writers and assembly-language programmers. “As strong as required but no stronger” is a difficult balancing act.

ARM/POWER Relaxed Memory Model

Now let’s look at an even more relaxed memory model, the one found on ARM and POWER processors. At an implementation level, these two systems are different in many ways, but the guaranteed memory consistency model turns out to be roughly similar, and quite a bit weaker than x86-TSO or even x86-TLO+CC.

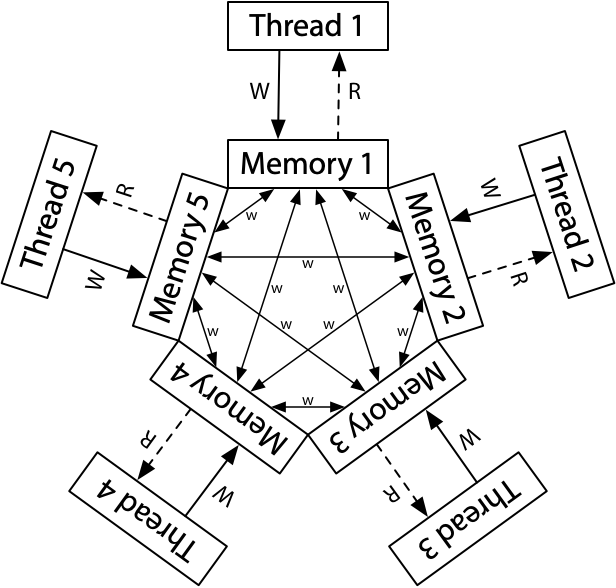

The conceptual model for ARM and POWER systems is that each processor reads from and writes to its own complete copy of memory, and each write propagates to the other processors independently, with reordering allowed as the writes propagate.

Here, there is no total store order. Not depicted, each processor is also allowed to postpone a read until it needs the result: a read can be delayed until after a later write. In this relaxed model, the answer to every litmus test we’ve seen so far is “yes, that really can happen.”

For the original message passing litmus test, the reordering of writes by a single processor means that Thread 1’s writes may not be observed by other threads in the same order:

Litmus Test: Message Passing

Can this program see

r1=1,r2=0?

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

x = 1 r1 = y

y = 1 r2 = x

On sequentially consistent hardware: no.

On x86 (or other TSO): no.

On ARM/POWER: yes!

In the ARM/POWER model, we can think of thread 1 and thread 2 each having their own separate copy of memory, with writes propagating between the memories in any order whatsoever. If thread 1’s memory sends the update of y to thread 2 before sending the update of x, and if thread 2 executes between those two updates, it will indeed see the result r1 = 1, r2 = 0.

This result shows that the ARM/POWER memory model is weaker than TSO: it makes fewer requirements on the hardware. The ARM/POWER model still admits the kinds of reorderings that TSO does:

Litmus Test: Store Buffering

Can this program see

r1=0,r2=0?

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

x = 1 y = 1

r1 = y r2 = x

On sequentially consistent hardware: no.

On x86 (or other TSO): yes!

On ARM/POWER: yes!

On ARM/POWER, the writes to x and y might be made to the local memories but not yet have propagated when the reads occur on the opposite threads.

Here’s the litmus test that showed what it meant for x86 to have a total store order:

Litmus Test: Independent Reads of Independent Writes (IRIW)

Can this program see

r1=1,r2=0,r3=1,r4=0?(Can Threads 3 and 4 see

xandychange in different orders?)

// Thread 1 // Thread 2 // Thread 3 // Thread 4

x = 1 y = 1 r1 = x r3 = y

r2 = y r4 = x

On sequentially consistent hardware: no.

On x86 (or other TSO): no.

On ARM/POWER: yes!

On ARM/POWER, different threads may learn about different writes in different orders. They are not guaranteed to agree about a total order of writes reaching main memory, so Thread 3 can see x change before y while Thread 4 sees y change before x.

As another example, ARM/POWER systems have visible buffering or reordering of memory reads (loads), as demonstrated by this litmus test:

Litmus Test: Load Buffering

Can this program see

r1=1,r2=1?(Can each thread’s read happen after the other thread’s write?)

// Thread 1 // Thread 2

r1 = x r2 = y

y = 1 x = 1

On sequentially consistent hardware: no.

On x86 (or other TSO): no.

On ARM/POWER: yes!

Any sequentially consistent interleaving must start with either thread 1’s r1 = x or thread 2’s r2 = y. That read must see a zero, making the outcome r1 = 1, r2 = 1 impossible. In the ARM/POWER memory model, however, processors are allowed to delay reads until after writes later in the instruction stream, so that y = 1 and x = 1 execute before the two reads.

Although both the ARM and POWER memory models allow this result, Maranget et al. reported (in 2012) being able to reproduce it empirically only on ARM systems, never on POWER. Here the divergence between model and reality comes into play just as it did when we examined Intel x86: hardware implementing a stronger model than technically guaranteed encourages dependence on the stronger behavior and means that future, weaker hardware will break programs, validly or not.

Like on TSO systems, ARM and POWER have barriers that we can insert into the examples above to force sequentially consistent behaviors. But the obvious question is whether ARM/POWER without barriers excludes any behavior at all. Can the answer to any litmus test ever be “no, that can’t happen?” It can, when we focus on a single memory location.

Here’s a litmus test for something that can’t happen even on ARM and POWER:

Litmus Test: Coherence

Can this program see

r1=1,r2=2,r3=2,r4=1?(Can Thread 3 see

x=1beforex=2while Thread 4 sees the reverse?)

// Thread 1 // Thread 2 // Thread 3 // Thread 4

x = 1 x = 2 r1 = x r3 = x

r2 = x r4 = x

On sequentially consistent hardware: no.

On x86 (or other TSO): no.

On ARM/POWER: no.

This litmus test is like the previous one, but now both threads are writing to a single variable x instead of two distinct variables x and y. Threads 1 and 2 write conflicting values 1 and 2 to x, while Thread 3 and Thread 4 both read x twice. If Thread 3 sees x = 1 overwritten by x = 2, can Thread 4 see the opposite?

The answer is no, even on ARM/POWER: threads in the system must agree about a total order for the writes to a single memory location. That is, threads must agree which writes overwrite other writes. This property is called called coherence. Without the coherence property, processors either disagree about the final result of memory or else report a memory location flip-flopping from one value to another and back to the first. It would be very difficult to program such a system.

I’m purposely leaving out a lot of subtleties in the ARM and POWER weak memory models. For more detail, see any of Peter Sewell’s papers on the topic. Also, ARMv8 strengthened the memory model by making it “multicopy atomic,” but I won’t take the space here to explain exactly what that means.

There are two important points to take away. First, there is an incredible amount of subtlety here, the subject of well over a decade of academic research by very persistent, very smart people. I don’t claim to understand anywhere near all of it myself. This is not something we should hope to explain to ordinary programmers, not something that we can hope to keep straight while debugging ordinary programs. Second, the gap between what is allowed and what is observed makes for unfortunate future surprises. If current hardware does not exhibit the full range of allowed behaviors—especially when it is difficult to reason about what is allowed in the first place!—then inevitably programs will be written that accidentally depend on the more restricted behaviors of the actual hardware. If a new chip is less restricted in its behaviors, the fact that the new behavior breaking your program is technically allowed by the hardware memory model—that is, the bug is technically your fault—is of little consolation. This is no way to write programs.

Weak Ordering and Data-Race-Free Sequential Consistency

By now I hope you’re convinced that the hardware details are complex and subtle and not something you want to work through every time you write a program. Instead, it would help to identify shortcuts of the form “if you follow these easy rules, your program will only produce results as if by some sequentially consistent interleaving.” (We’re still talking about hardware, so we’re still talking about interleaving individual assembly instructions.)

Sarita Adve and Mark Hill proposed exactly this approach in their 1990 paper “Weak Ordering – A New Definition”. They defined “weakly ordered” as follows.

Let a synchronization model be a set of constraints on memory accesses that specify how and when synchronization needs to be done.

Hardware is weakly ordered with respect to a synchronization model if and only if it appears sequentially consistent to all software that obey the synchronization model.

Although their paper was about capturing the hardware designs of that time (not x86, ARM, and POWER), the idea of elevating the discussion above specific designs, keeps the paper relevant today.

I said before that “valid optimizations do not change the behavior of valid programs.” The rules define what valid means, and then any hardware optimizations have to keep those programs working as they might on a sequentially consistent machine. Of course, the interesting details are the rules themselves, the constraints that define what it means for a program to be valid.

Adve and Hill propose one synchronization model, which they call data-race-free (DRF). This model assumes that hardware has memory synchronization operations separate from ordinary memory reads and writes. Ordinary memory reads and writes may be reordered between synchronization operations, but they may not be moved across them. (That is, the synchronization operations also serve as barriers to reordering.) A program is said to be data-race-free if, for all idealized sequentially consistent executions, any two ordinary memory accesses to the same location from different threads are either both reads or else separated by synchronization operations forcing one to happen before the other.

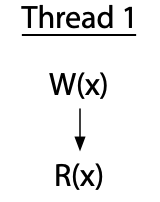

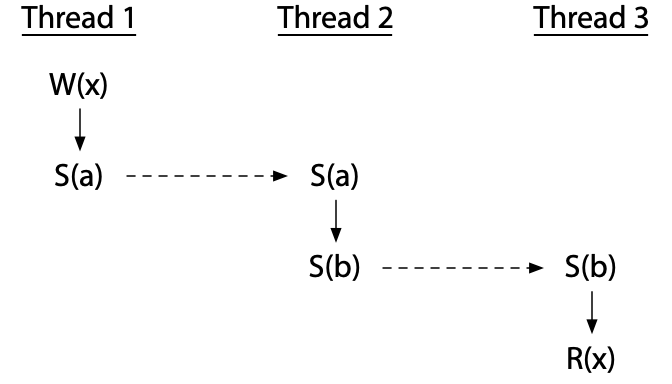

Let’s look at some examples, taken from Adve and Hill’s paper (redrawn for presentation). Here is a single thread that executes a write of variable x followed by a read of the same variable.

The vertical arrow marks the order of execution within a single thread: the write happens, then the read. There is no race in this program, since everything is in a single thread.

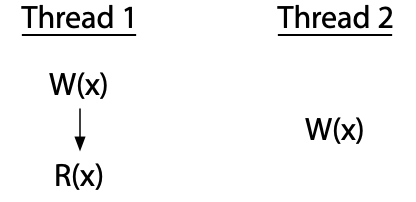

In contrast, there is a race in this two-thread program:

Here, thread 2 writes to x without coordinating with thread 1. Thread 2’s write races with both the write and the read by thread 1. If thread 2 were reading x instead of writing it, the program would have only one race, between the write in thread 1 and the read in thread 2. Every race involves at least one write: two uncoordinated reads do not race with each other.

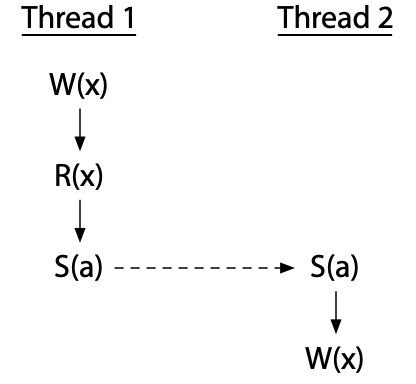

To avoid races, we must add synchronization operations, which force an order between operations on different threads sharing a synchronization variable. If the synchronization S(a) (synchronizing on variable a, marked by the dashed arrow) forces thread 2’s write to happen after thread 1 is done, the race is eliminated:

Now the write by thread 2 cannot happen at the same time as thread 1’s operations.

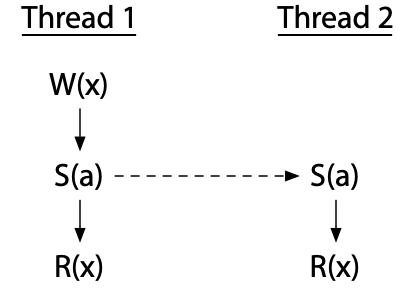

If thread 2 were only reading, we would only need to synchronize with thread 1’s write. The two reads can still proceed concurrently:

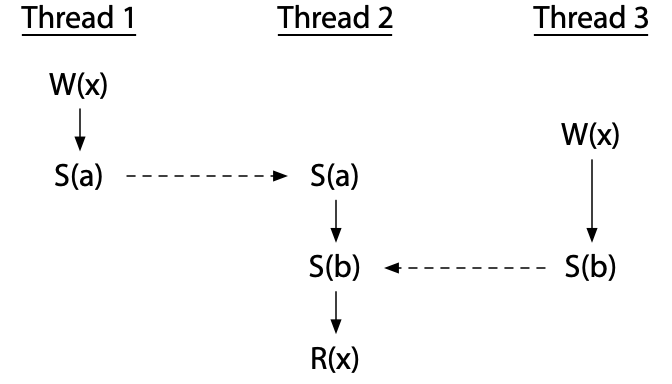

Threads can be ordered by a sequence of synchronizations, even using an intermediate thread. This program has no race:

On the other hand, the use of synchronization variables does not by itself eliminate races: it is possible to use them incorrectly. This program does have a race:

Thread 2’s read is properly synchronized with the writes in the other threads—it definitely happens after both—but the two writes are not themselves synchronized. This program is not data-race-free.

Adve and Hill presented weak ordering as “a contract between software and hardware,” specifically that if software avoids data races, then hardware acts as if it is sequentially consistent, which is easier to reason about than the models we were examining in the earlier sections. But how can hardware satisfy its end of the contract?

Adve and Hill gave a proof that hardware “is weakly ordered by DRF,” meaning it executes data-race-free programs as if by a sequentially consistent ordering, provided it meets a set of certain minimum requirements. I’m not going to go through the details, but the point is that after the Adve and Hill paper, hardware designers had a cookbook recipe backed by a proof: do these things, and you can assert that your hardware will appear sequentially consistent to data-race-free programs. And in fact, most relaxed hardware did behave this way and has continued to do so, assuming appropriate implementations of the synchronization operations. Adve and Hill were concerned originally with the VAX, but certainly x86, ARM, and POWER can satisfy these constraints too. This idea that a system guarantees to data-race-free programs the appearance of sequential consistency is often abbreviated DRF-SC.

DRF-SC marked a turning point in hardware memory models, providing a clear strategy for both hardware designers and software authors, at least those writing software in assembly language. As we will see in the next post, the question of a memory model for a higher-level programming language does not have as neat and tidy an answer.

The next post in this series is about programming language memory models.

Acknowledgements

This series of posts benefited greatly from discussions with and feedback from a long list of engineers I am lucky to work with at Google. My thanks to them. I take full responsibility for any mistakes or unpopular opinions.